Very few people outside of the tech community tend to realize, that 3D printing is a technology that had been talked and hypothesized about since the 1970s.

The first recorded mention of 3D printing can be traced back to an article written by famed technology columnist David E. H. Jones for the New Scientist journal in 1974.

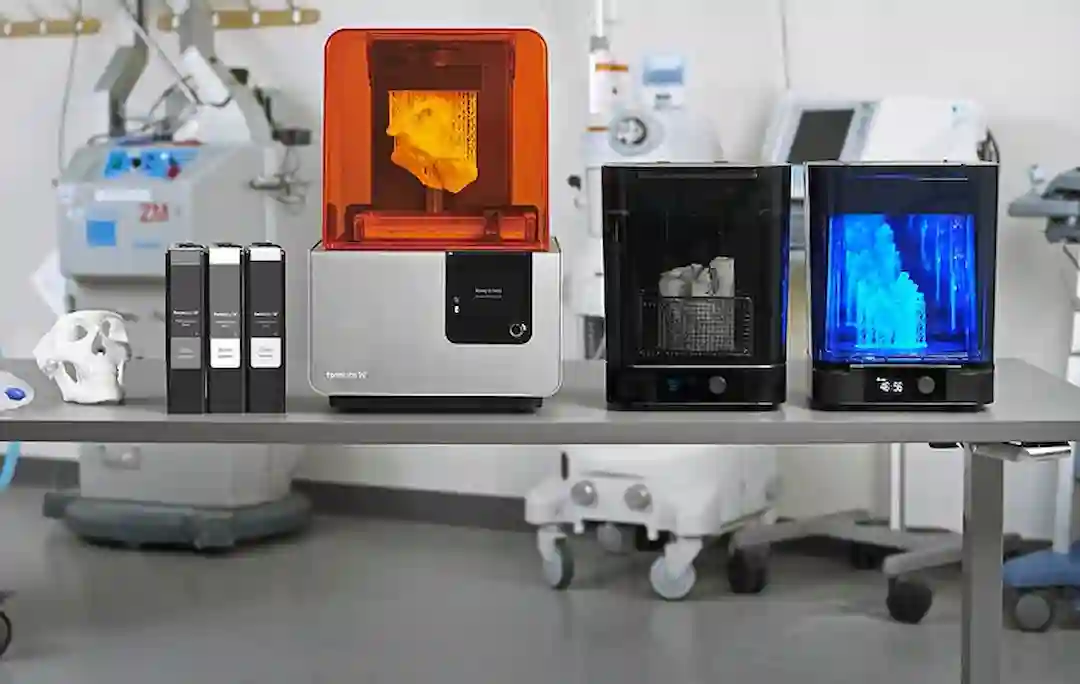

Written under the pseudonym, “Daedalus”, David E. H. Jones explained in his article, the possibility of forming and creating 3D models by shining precise lasers onto a vat of photosensitive monomers. This idea would serve the basis of the very first 3D printers less than a decade later.

Origins of 3D printing – why it was invented

It was not until 1981 that the first patent to describe the principle technology of a resin-curing 3D printer was applied for with the US Patent Office. Doctor Hideo Kodama of Nagoya Municipal Industrial Research Institute applied for the patent of two methods of 3D printing objects. He called it rapid prototyping at the time. A term that carried on today to mean the creation of the initial design of a product or object intended for proof of concept and pre-production testing.

Both approaches utilized the photo-hardening property of certain thermosetting plastics when selectively exposed to ultraviolet light by way of either a mask pattern or through the use of a scanning fiber transmitter.

Alas, however, the patent application was rejected by the patent office for failure to file the patent within the one-year deadline. Despite Doctor Kodama’s failure to secure a patent, the intrigue in this then-novel technology by no means diminished.

Three French scientists: Jean-Claude André at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). Olivier de Witte at CILAS, and Alain le Méhauté at Compagnie Générale d’Electricité (CGE, now Alcatel-Alsthom), collectively worked on a stereolithography-based 3D printer design. The trio presented the design to the CNRS in 1984, only to have it turned down. CNRS reluctantly concluded that the technology greatly lacks viable areas of application. Their patent filing too was destined for inconsequential doom, as both CILAS and CGE abandoned the project along with the patent filing.

For 3D Printing then, it would seem that the third time was indeed the charm.

World’s first rapid prototyping 3D printer

Charles “Chuck” Hull, globally recognized now as the pioneering founder of 3D printing, forming the company, 3D Systems Inc. He filed for his patent for “Stereolithography” in 1984, just three weeks after the French trio.

Hull’s idea for the resin-curing technique was developed out of his frustration at the lead times that were common back then for the manufacture of custom parts. Hull was convinced that parts could be manufactured by curing resin via the UV lamps already used to cure furniture topcoats.

The tabletop and furniture manufacturer that he worked for provided him with a small lab to test and work on his idea. Thankfully, for the future of 3D printing, Chuck’s patent was granted in 1986.

Hull founded his now globally recognized company in the same year and produced the first commercially available stereolithography-based 3D printer, the SLA-1, in 1988.

3D printing technology has only just begun to truly come within the reach of the average consumer. Even now, experts believe that the proliferation of affordable 3D printers has ways to go before the technology could be considered mainstream. If we were to ask the average consumer when they first heard about 3D printing, surely the answer would not be more than five years, or at most, a decade and a half ago.

Inventions of different types of 3D printing technologies

Just as Charles Hull’s SLA-1 was hitting the market in 1988, Carl Deckard, a University Of Texas (Austin) undergraduate, was busy developing an entirely different method of printing 3D models.

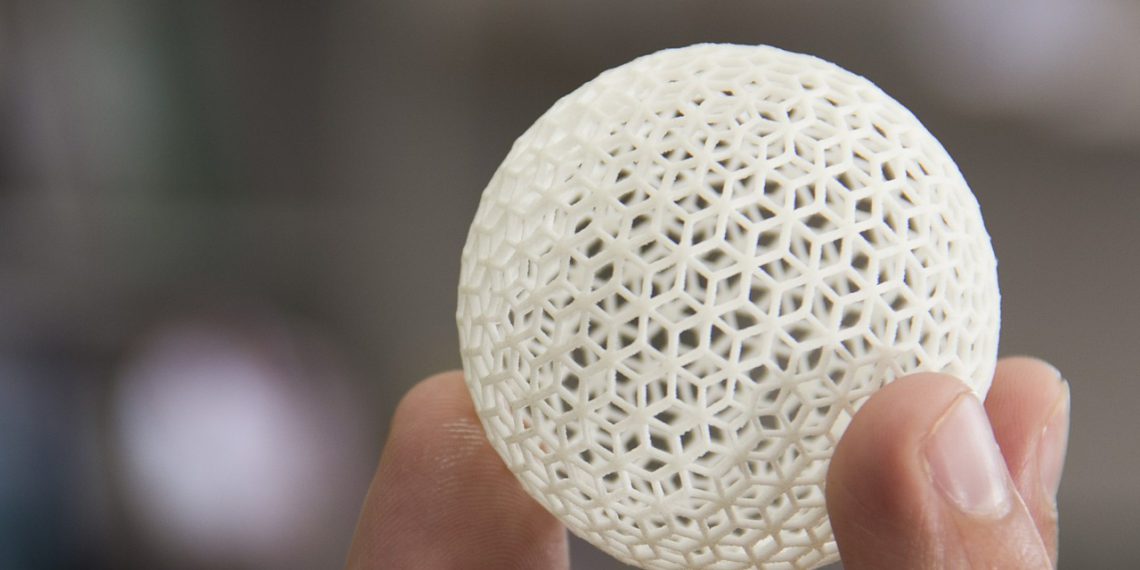

By using lasers to selectively bond together granules of powder, Deckard was able to demonstrate what he called SLS, Selective Laser Sintering, as a viable method of rapid prototyping. While Deckard’s first machine, “Betsy” was only able to produce small pieces of plastics…still, this was enough for Deckard to continue refining his design throughout his Masters and Ph.D. In doing so, he acquired the help of Professor Joe Beaman at UT-Austin till he applied for a patent on SLS technology in 1994.

SLS would still take a long time to become commercially available. A similar technology, but one that worked with metal powders, Selective Laser Melting, was developed at the Fraunhofer Institute in Auchen Germany in the 1995. Additive Manufacturing makers EOS deposited the name Direct Metal Laser Sintering to the same process. This breakthrough allowed for 3D printing to finally be seen as a means of industrial manufacturing.

Birth of FDM 3D printers

In 1989, Steven Scott Crump, after a frustrating attempt to craft a toy frog for his daughter made from a hot glue gun, invented fused deposition modelling (FDM). He later co-founded one of the juggernauts of the 3D printing world, Stratasys, with his wife Lisa Crump. The Crumps filed for a patent on FDM in the same year.

Slowly but surely, the moniker of rapid prototyping began to lose its value for the underlying technologies. Inventors and innovators had begun to view 3D printing as a means of efficient, precise, additive and rapid manufacturing. While its value as a prototyping technology has only increased with time, it is arguably the vaste range of possibilities that it enables which has baffled and amazed even the most ardent of skeptics.

Today rapid prototyping is use by inventors, engineers, and developers as part of the manufacturing or development workflow.

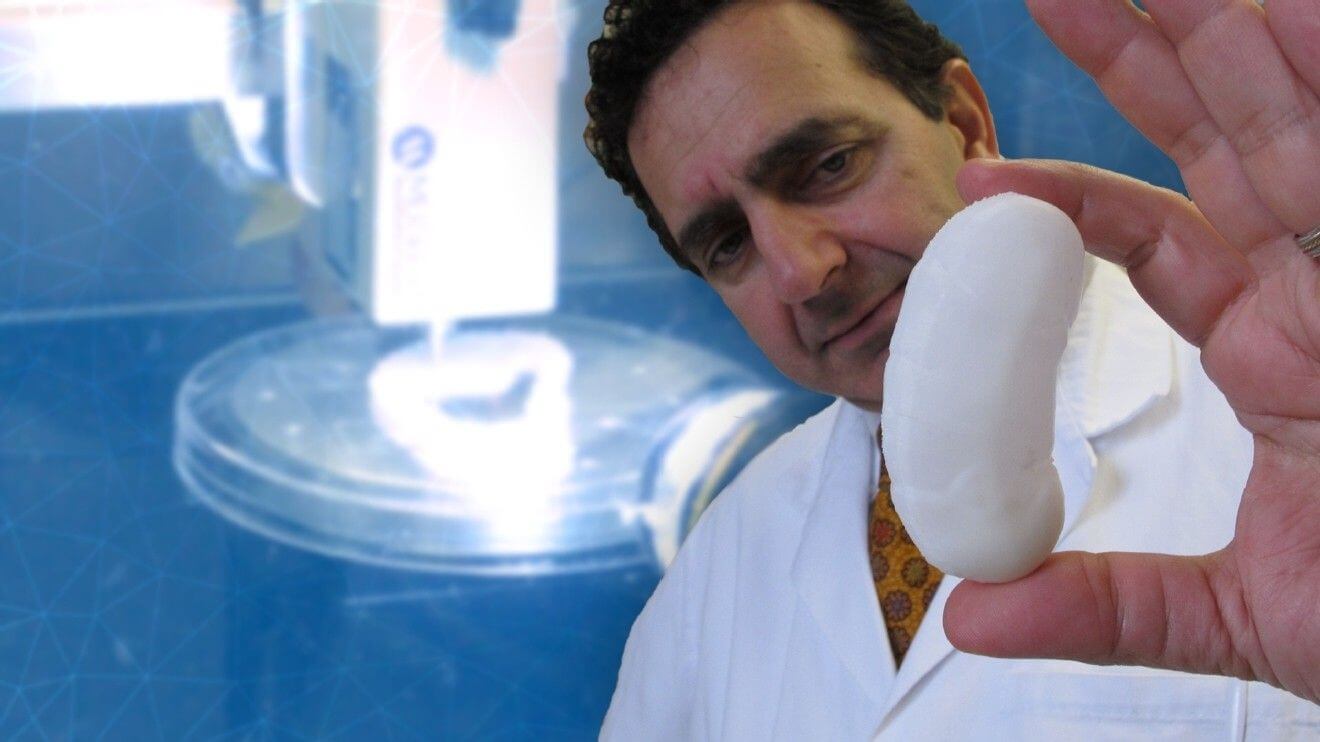

First application for Bioprinting

One such innovation reared its head onto the media in 1999. Doctor Anthony Atala of the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine used a modified inkjet printer with biological tissue forming material, to successfully 3D print a synthetic scaffold of a human bladder. Mr. Atala’s work paved the way for bioprinting. He and his team successfully transplanted 3D printed human bladders in at least seven young patients by 2006.

Birth of the RepRap Project

No account of the history of 3D printing could ever be complete without mention of Dr. Adrian Bowyer.

Doctor Adrian Bowyer of University of Bath, England founded the Open-source Replicating Rapid prototyper (RepRap) project in 2005. The goal was to design a 3D printer that could completely self-replicate all its parts, so that anyone with access to a reprap printer could print and assemble another completely functional 3D printer. This self-replicating ability would allow for the proliferation of 3D printers as desktop manufacturing units among the masses and enable distribution of manufacture, instead of distribution of manufactured goods.

Now made up of hundreds of collaborators around the world, the reprap project has shown no signs of slowing down. Already capable of producing all plastic parts of another reprap printer, the project continues to work towards its goal of true self-replication by one day being able to reliably print its own circuit boards as well as metal components by use of different extruder heads.

The RepRap project, by virtue of its open design guidelines, kickstarted the market for extrusion-type affordable DIY 3D Printers.

Consumer brands such as Prusa, Makerbot, Micro, iTron to name a few, would simply not exist had there been no RepRap.

Recent developments in the 3D printing industry

Crump’s key patent on FDM technology expired in 2009. Makers of 3D printers jumped on the opportunity. Complementing the work done by the RepRap project, the expiration opened up FDM technology to even entry-level 3D printers and the prices started to nosedive.

Similarly, the SLS patent expired in 2014 and the market finally opened up for relatively afforadable Sinter-type 3D printers.

As these industry-process patents are slowly but surely coming to an end, competition is bringing down prices ever further. Today, one can affordably consider buying an FDM and SLA printer at the consumer level. And SLS and SLM printers at the industrial level.

New uses of 3D printing

Owing to their manufacture promise, 3D printers were adopted by the fashion industry, food industry and construction industry over the course of the first decade of the new century.

While fashion and fine dining are new additions. Work on construction-based 3D printers had been ongoing since at least the 90s, with the Contour Crafting extrusion-based technique being developed in 1995 by Behrokh Khoshnevis of University of Southern California.

In 2005, Enrico Dini in Italy patented the D-Shape technology that employed a massive scaled powder jetting bonding technique.

The future of 3D printing

3D printers continue to be used to innovate in sectors that could never have even conceived of benefiting from “Prototyping” technology. Be it food, construction, prototyping, manufacture, medicine or bio-printing. 3D printing was not developed for this.

In true form of unleashed potential, from its humble beginnings as a tech that no organization could see an application for, 3D printing has become a buzzword worthy of its hype. At this rate, we may realistically be headed to live in a world idealized by the RepRap founders. One where distribution of manufacture enables all, and not just the privileged or fortuitous few.

3D printing may not have been developed with such explosive goals in mind. Regardless, however, 3D printing most certainly seems destined to meet them.

How long ago did you first hear about or seen your first 3D printer? Let us know in below.